Unpacking the Table

It’s Thanksgiving and Summer Walker’s trending yet again, not for her highly anticipated album but for a voicemail where she drunkenly asked Rich The Kid to be saved under “Pizza Hut” in his phone—he’s engaged. It feels befitting to open this conversation with a little cultural chaos because much like the humor and music discourse surrounding Walker’s rollout of Finally Over It, Thanksgiving carries its own mythology that crumbles the moment you look a little closer.

Just as fans have watched Walker rewrite her story without London On Da Track ( a stark contrast to the harmonious era that produced Over It) the story we’ve been fed about Thanksgiving smooths over a partnership that was anything but harmonious. The Plymouth colonists and the Wampanoag tribe did share a moment of harvest, yes. But unlike Summer and London’s studio synergy, their “collaboration” wasn’t rooted in amalgamation, mutual respect, or even choice. And much like Walker’s new album title suggests, the years that followed shifted the narrative entirely. The Pilgrims were spotlighted for generations to immortalize as the heroic founders of a new nation, while Native people who’d already steward this land were erased from their own story.

It simple, what we now call “Thanksgiving” has roots in violence. Several times throughout history, days of “thanksgiving” were declared after massacres of Native people. One of the earliest examples came in 1637, when Massachusetts Colony Governor John Winthrop announced a day of thanksgiving following the murder of around 700 Pequot people. Many historians cite this as the first official reference to a “thanksgiving” ceremony… a stark contrast to the kumbaya classroom stories we grew up on.

That Thanksgiving story we loved as children — myself included, though as a Black kid my excitement was always less about painting our faces and dressing in cut-up paper bags and more about my Nana’s mac and cheese and the time off school — was rooted in an incessant need for students to mimic Native American tribes. And don’t even get me started on my hometown baseball team, the Indians. It was guided cultural appropriation, never a true retelling of harmony. It was a myth covering a painful truth: prayer and feasting built on the slaughter of Native people.

Before the Feast, There Was Her

Now, when we shift to the Middle Passage and how Black Americans come to this holiday, things get even more layered. For Black people, Thanksgiving carries a different kind of weight and I ain’t talking about the numbers you see on the scale chile! We, too, recognized Thanksgiving as a distorted celebration. During slavery, enslaved people cooked lavish meals under brutal conditions only to watch their enslavers eat joyfully. The scraps: the things they wouldn’t dare serve on their own tables, became our salvation.

And at the center of that survival were Black women.

Black women were the hands that stirred the pots, seasoned the food, nursed the babies, and held together households that refused to see their humanity. They were the early culinary architects of what we now call “soul food,” turning discarded cuts and overlooked ingredients into dishes that brought comfort to people who were denied basic dignity. Cooking wasn’t just labor through food, Black women sustained not only bodies but spirits.

Imagine being in the field all day, then preparing a holiday feast you were never invited to enjoy, only to eat whatever leftovers were tossed aside. Yet somehow, through skill and ingenuity, those same scraps became cornerstones of our tradition. Chitlins, collard greens, candied yams, cornbread, turkey necks, rice pudding, etc. weren’t just meals — they were survival stories. They were the flavors of community. They were the heartbeat of the quarters.

In many enslaved families, the Black woman was the matriarch long before we called her Big Mama or Nana or Madea. She was the glue. Holidays, even when they weren’t recognized as holidays for Black people, became moments where she created tiny pockets of joy in the midst of terror. She fed whole families off scraps the way she fed entire generations of strength she was never credited for.

“Be present in all things and thankful for all things”

Black women made Thanksgiving a cultural touchstone long before it was ever something we claimed out loud.

A Black Women Thanksgiving in Film

When we shift from the real kitchens of Black women to the way their labor shows up on screen, the story gets even more complicated. Hollywood has always known the power of a Black woman in the kitchen…maybe a little too well. For decades, film has pontificated, exaggerated, and packaged Black women’s contributions into tropes that were easy to consume but rarely accurate. We’ve seen the Mammy archetype: the loyal, apron-wearing caretaker who cooks, cleans, and comforts everyone except herself.

A brief intermission for the heavy negro sigh…recycled like a worn-out recipe card

From early cinema all the way through mid-century film, this character was framed as nurturing but never fully human, always serving but never served. And yet, behind that flattened image was a truth Hollywood refused to tell: Black women held entire communities together through food and wisdom a strength that deserved more than a caricature.

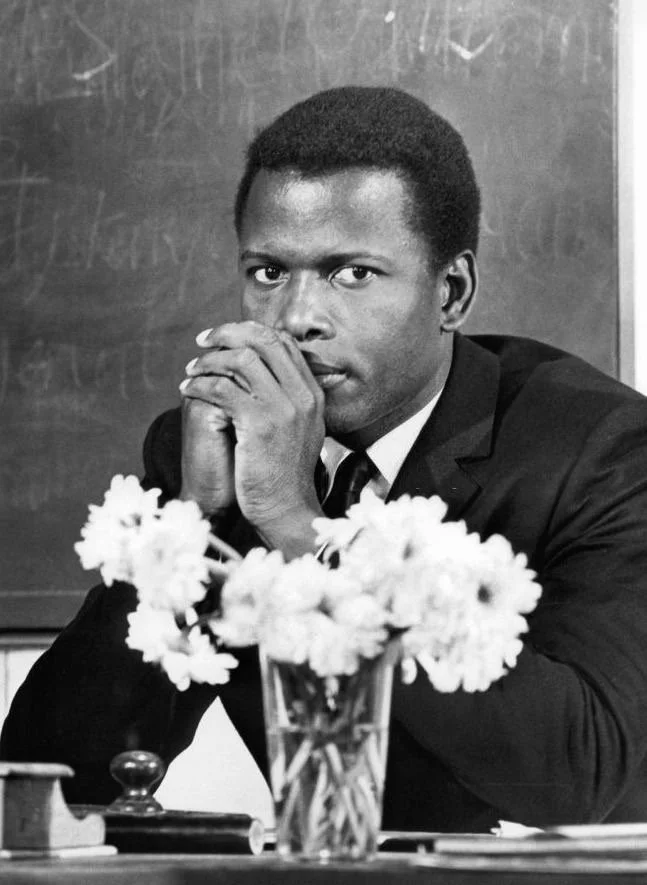

Then came films that tried to peel back the layers. When Sidney Poitier appeared in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, or when Imitation of Life introduced the complexities of Black mothers we began to see glimpses of the real emotional labor Black women carried.

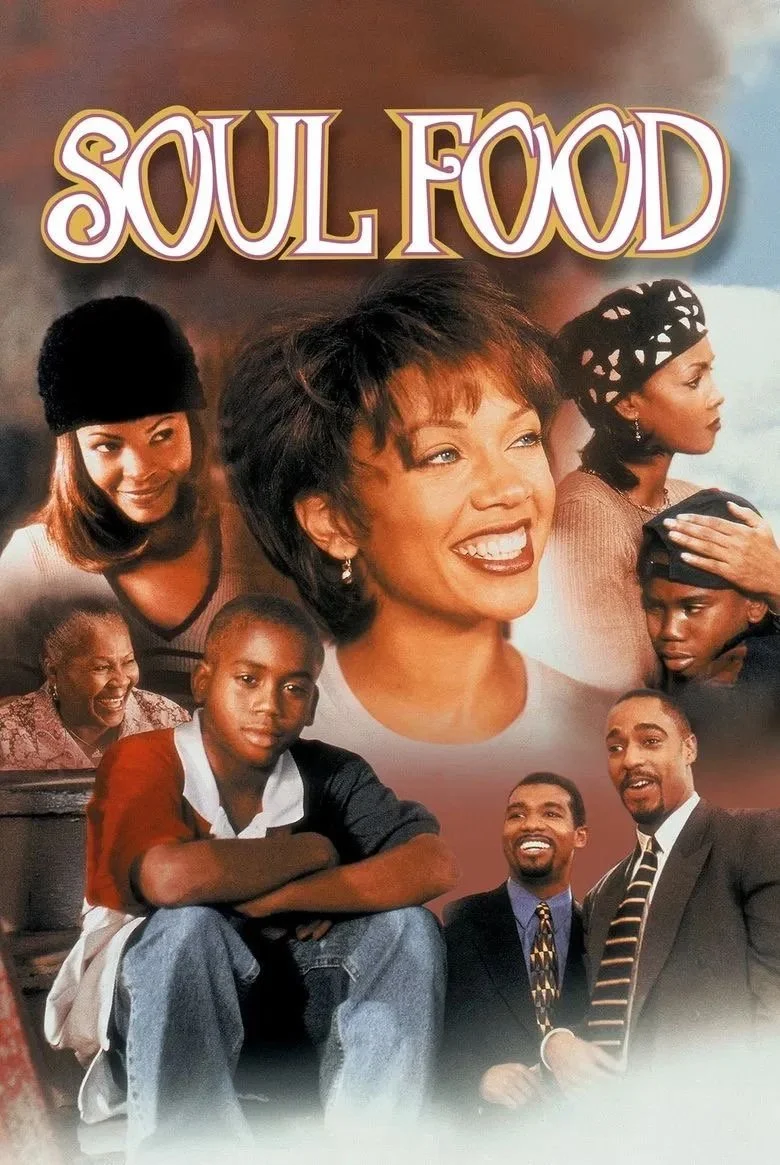

And then, Soul Food changed the game (at least for me when it came on late at night on BET) With Big Mama at the center, Soul Food gave us a matriarch who wasn’t a stereotype she was a mirror. Her children our make believe aunties in our heads and her grandson a true manifestation of the love we had for our own grandmothers wrapped the Black community like a quilt knitted from our ancestors. Big Mama was a woman who fed her family with her hands and held them together with her heart. Her Sunday dinners weren’t a backdrop; they were the story. The kitchen was her domain, not because she was expected to serve, but because it was where she transformed struggle into nourishment, chaos into communion, leftovers into legacy.

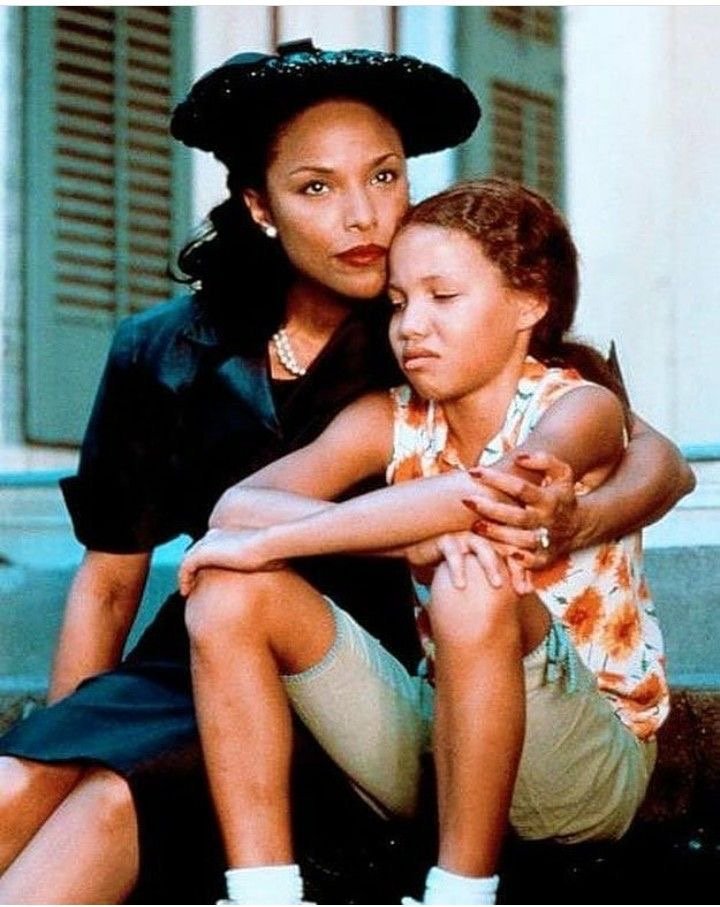

Films like Crooklyn, Eve’s Bayou, Almost Christmas, and This Christmas continued the work, showing Black women not just as cooks, but as creators, disciplinarians, nurturers, visionaries the architects of their home. Through film, we’ve watched the cultural idea of the Black matriarch evolve. The industry has exaggerated her, misunderstood her, even mocked her but one truth always survives the script: Black women are the heartbeat of the household and every on-screen kitchen we’ve ever loved began with the real ones they kept alive.

Today, Black Americans are working to dismantle these tropes and reimagine the traditions attached to them. Big Mama would want the family together, yes — but she’d also want us happy. So if your nosy aunty starts getting a little too invested in your life, return the shade and pay her dust. And if cousin’nem asks you to step out for “that walk,” go ahead and go! I promise Mama will understand.

This holiday season, we’re gathering with intention and feasting with purpose. So if you need to save that man’s name under “Little Caesar’s,” do it. It’s Thanksgiving! Have your cake and eat it too. Sike nah… no more listening to Summer Walker or cousin faith for that matter chile

To all my readers: Happy Thanksgiving!